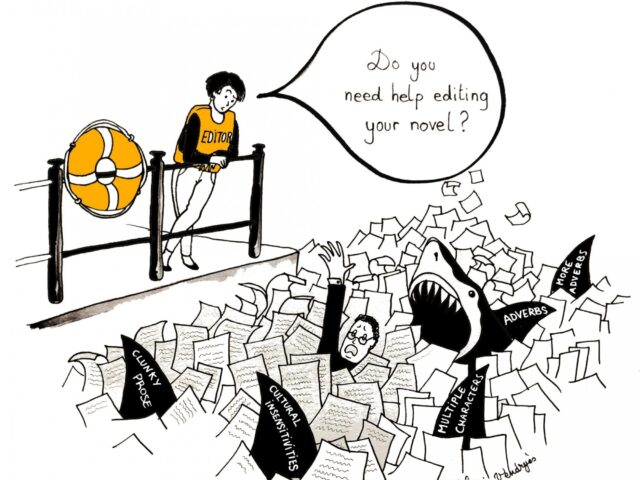

Quite often – a couple of times a month – I’ll get an email from someone asking me about ‘hybrid’ publishers. Are they good? Are they bad? What’s the difference between them and a vanity publisher? Should I invest my cash? And how much to invest? And what can I expect to back in terms of sales and royalties?I’ve put off writing an answer because the area is complex and just doesn’t lend itself to easy guidelines. So let me say upfront, this email will not provide you with any certainties. In every case, you need to do your own research and figure out what’s right for your situation. I don’t know what’s right for you.That said, let’s start off easy, with some definitions:Traditional publishingTrad publishing comes big or small. You can access it with or without an agent. Pretty much every book you find in a regular bookshop comes via a traditional publisher of some description, though of course the same books are available online as well.The one thing that really defines traditional publisher is that the author pays nothing and will expect to receive some money. With bigger publishers, you’ll get an advance plus (if book sales are sufficient to pay out the advance) royalties as well. With smaller publishers, advances may be small or even zero, but you’ll still get royalties on sale. And you, the author, never pay anything. I mean that literally. I’ve been an author for more than twenty years and I have never once paid a publisher any money for anything. I’ve never paid my agent. I’ve never even paid for a lunch. The flow of money is always from them to you. That’s trad publishing.Self-PublishingSelf-publishing, in its truest sense, means that you take responsibility for writing, editing, designing, producing, distributing and marketing your book.That doesn’t mean you have to do all those things personally. It’s not just fine but positively sensible to outsource certain tasks to experts. Jericho Writers offers great editing and copy editing services. Cover designers can create great covers for you. And Amazon and other online retailers offer the world’s most extraordinary distribution platform. A solo self-publisher today can access – easily – more readers than I ever could with my first book, which was a super-lead title sold by a major Big 5 publisher, with a ton of marketing spend behind it. (And yes, there’s a difference between the ability to access readers and selling books - but you need the first to achieve the second.)In financial terms, self-publishing can be defined as this: You own your work. No one else has a claim on your royalties. You have complete authority for every aspect of the book (text, design, blurb, pricing, etc). The costs and the revenues all flow through to you.(And, OK, to be really precise about this, some online distribution services such as Draft2Digital take a percentage of sales for their distribution efforts, but you can choose to operate direct at any point. Arrangements like that are a convenience, nothing else.)Book productionWhere it starts to get tricky is that some firms offer to bundle the whole book production process together for you. Lulu, for example, says: “Whether you need 1 copy or 1,000 copies, you can create and print bookstore quality books online with Lulu.”Originally, in fact, Lulu was mostly there to help you simply produce a nice-looking book. My sister, for example, took some of the best photos from my father’s memorial service and put together a beautifully produced photobook to commemorate the day. Kate didn’t think she was publishing anything, and the purpose was never to make sales. Lulu just offered a slick online tool to get a great-looking book. The book was never on sale, nor did we want it to be.A pure book production company will charge a set amount for delivering a certain mumber of books. The amount will vary with book length, format, number of illustrations and so on, but in the end, it’s not all that different from ordering canned fish. You specify what you want. You agree a price. You take delivery. What happens next is up to you. Services that do an honest job and charge nothing in terms of ongoing royalties include Scribe Media and AuthorImprints.Inevitably, however, plenty of people who use these services also have an ambition to make sales, so many such companies don’t just offer a ‘print and deliver’ service, they offer a ‘publishing’ service too. In most cases, that means your book will be uploaded to Amazon and the other online retailers and made available for sale, most likely as both print and ebook.When something that is basically a production service starts to get branded as a publishing service, things get murky. (And, just to be clear, I think Lulu is fine. I’ll have some nasty things to say about some companies, but Lulu isn’t one of them.)Vanity publishingVanity publishing is best understood by its ethics – or lack of them.The classic vanity publisher is one that purports to operate like a traditional publisher but is nothing of the sort. There’s one toxic British vanity publisher which invites writers to submit work, just as though this were a trad publisher looking for manuscripts. But when it comes to it, you’ll be told, ‘Hey, congrats, we loved your book. But you know what? This is a really tough market and our editorial board didn’t quite have the confidence to take this on in the regular way. But we’d love to handle this via our partnership process and …’Inevitably, the nature of the ‘partnership’ is that you end up paying a lot of money for the firm to produce, distribute and market the book, with sales royalties split between the two of you. (It’s that royalty split which allows them to claim a partnership exists.) The trouble this causes is many-fold:The vanity publisher has a strong financial incentive to take on any old rubbish. If they can convince an author to pay up, the firm makes money. So they honestly wouldn’t care if the were sent an old dishwasher manual. (I’m not making that up, by the way, I once did send one of these firms an old dishwasher manual. They were very excited to accept it for publication.)Real bookshops know that these firms have a strong incentive to take any old rubbish, so they don’t want to stock the books. That doesn’t apply to Amazon, of course, which essentially doesn’t vet the material being uploaded, but it does apply to all physical bookstores. There’s a hard upper limit to how much cash writers are willing to hand out in exchange for ‘publication’, so publishers can increase profits by saving money on editing, copyediting, cover design, and everything else. That means the quality of books being produced is likely to be poor, even setting aside the lack of quality control when it comes to the actual text. Marketing is hard even where good books are concerned. Marketing rubbish is effectively impossible. Since vanity publishers mostly publish rubbish (plus some good texts in the mix as well), they are not about to do any real marketing. So yes, they may offer you some marketing services for a premium price, but those services are not likely to be effective. They’re not intended to be effective; they’re intended to make you part with your cash.The ultimate problem here is simply the dishonesty. Vanity publishers aim to sell their (typically shoddy) service, while persuading writer that what they’re getting is very largely the same as they’d get from a trad publisher.I’ve seen some absolutely loathsome behaviour from vanity publishers over the years – and the list of culprits is sadly long.Ethical hybrid publishersWhich brings us to the central question in all of this:Is there such a thing as a full-service, ethical, hybrid publisher?To be specific, we’re looking for a publisher, where:You, the author, would be paying a significant sum upfront and a significant share of ongoing royalties.In exchange, you wouldn’t just get a pure book production service, or a pure production / distribution one. You’d also be getting one that looked to market and sell your booksThe answer is yes, such services do exist.Names that are usually mentioned positively in this context are She Writes Press, Girl Friday, Greenleaf and (in the UK) Matador. Please note, I’m reporting here on the general industry consensus. I haven’t recently vetted those companies and can’t guarantee that what they offer YOU will be right for your needs.But before you rush to send your book to these outfits, you need to note:They are somewhat selective. You can’t be an ethical publishing service without refusing a proportion of the books that come your way.The upfront fees can be large. She Writes Press charges $8,500 for a service with additional fees on top. You could self-assemble that core service yourself for very much less money – and with highly acceptable outcomes in terms of quality. Most authors lose money, and maybe a lot of it. With the best companies out there, perhaps 10-25% of authors recoup their investment. Maybe even 33%. The rest all lose. For very few will the investment make financial sense, when your time and effort are taken into account.When to consider an ethical hybrid publisherBy now, you’ll understand why I – and most people like me – are deeply dubious of any hybrid publisher. Wherever possible, my strong preference is to steer authors towards proper trad publishing or proper self-publishing. Both of those routes are great. They offer different things and pose different challenges, but the basic pathways are sound as a pound.Equally, if you just want a nicely produced photobook, then go to a Lulu or similar and bodge one together. It’s simple and fun.But that still leaves a whole heap of authors whose books aren’t salesy enough for a trad publisher and whose talents or ambitions don’t run to self-publishing. What then?Well, I think there is a role for ethical hybrid outfits. I remember one client of ours who had spent almost fifty years as a nurse in her home community of Leicester. She wrote a memoir about that experience, which was true, touching, nostalgic, wonderful – the record of a good life, well spent. But there was nothing especially remarkable in the story. A big commercial publisher couldn’t possibly have seen a way to strong five-figure sales, or even four-figure sales. The trad route essentially doesn’t exist for books like that.At the same time, the writer was elderly and clearly not about to start wrestling with all the tech and interfaces involved in self-publishing. So, with our encouragement, she hooked up with Matador, a reputable, full-service, hybrid. I know the lead publisher there and know him to be a decent man. Critically – this is just essential – he’s honest with his clients. He tells them what to expect. He tells them that they’ll probably lose money. The process feels like explanation, not selling. As I understand it, She Writes Press for example takes the same, full disclosure approach.Personally, I think writing a memoir is an utterly brilliant thing to do – and who cares if the resultant work isn’t one that a trad publisher wants to handle?If you write a memoir, then please, get it printed. Get enough copies that you and your loved ones can all have one. Get the things handed out like teacakes at your funeral. If you want to do that by handling the tech yourself, then fine. If not, pay someone. Either way, it’s a wonderful thing to do.As it happens, my Leicester nurse had a ton of contacts in her area and proved to be a capable saleswoman. She sold upwards of 500 copies and earned back what she’d spent. But if she’d sold nothing, but given away 500, that would still have been a great outcome. What matters was the book, not the revenue.There are other examples where it might make sense for you to just pay someone to handle things. Let’s say you run some kind of consultancy business. You think that authoring a book would prove your qualifications and be a great thing to hand out to potential clients. In that case, you’re intending to monetise the book in a way that lies outside of book sales and you just need to deal with book production and swiftly and cost effectively as you can. Snakes and angels: how to tell the differenceAs I warned you early on, it’s hard to give easy conclusions here, but here are some:Trad publishing is always a perfectly honourable route to publication The same goes for self-publishing. I like both routes. If you just want a physical book produced, then go for it. The key here is that there’s no royalty-sharing – there’s no pretence of this being a joint publishing venture. Most ‘hybrid publishers’ are deeply sleazy. To repeat: a hybrid arrangement is one where you pay upfront and via royalties. The majority of these services are, in my view, deeply deceptive and fundamentally dishonest. I know many, many authors who have been injured by them. That said, there are some honest hybrid publishers and there are some circumstances where such an arrangement could easily make sense for you. I’ve mentioned memoir and business books, but there’ll be plenty of other situations too. Hybrid publishing – with the right publisher – can make sense for some people some of the time. If you think you might be in that category, then do your research, ask questions, and trust your gut. If you feel you’re getting truthful and full disclosure answers to your questions, your putative publisher is probably honest. If you just feel heavily sold to, then treat that publisher like a rat bulging with buboes. If in doubt, run. Be pessimistic about your chances of making sales. when you are figuring out the finances of your venture, run the figures assuming that you’ll sell 50 copies. For many authors, that 50 copy figure will prove to be a gross overestimate. Books are hard to sell. What happens if you sell none? Can you live with that? Would the venture still be worthwhile? In publishing, you have to assume the worst because the worst is really quite likely to happen.That’s it from me. And lordy me, this email’s a whopper, but the topic’s important – and difficult.