Developmental editing. Structural editing. Line editing. Copy editing. Proofreading.

Yes, we know: you’ve written a manuscript. You know it needs some kind of professional help. But what kind of help? Copy editing or line editing? Structural editing or developmental support? There seem to be so many options to choose from.

But never fear. We’ll tell you exactly what each of the different types of editing are – and offer some suggestions on what editing you do/don’t need right now.

The good news is that, quite often, you need less editorial input than you might think. (The bad news is that you have to put in a lot of hard graft instead…)

What Are The Different Types Of Editing?

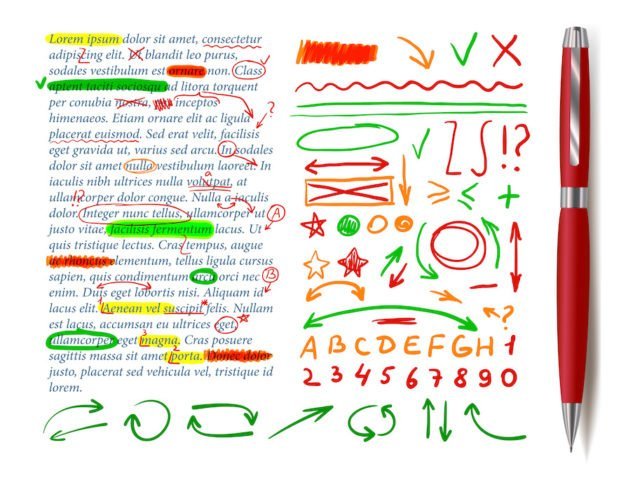

Developmental editing: checks concept, plot coherence, and character development/arc.Structural editing: identifies issues with plot, pacing, characters, settings, themes, writing style.Line editing: looks at details line by line.Copy-editing: is much as above, except with less attention to line-by-line correction of clumsy writing.Proof reading: looks for simple typos or errors in the text.

How Editing Works

Before we go any further, it’s worth explaining the editorial heirarchy. Essentially you go from large to little, from structural to detailed.

So it’s like building a house: you start with foundations, walls and roof. Then you start thinking about doors and windows. Then you start thinking about paints and wallpapers. Last, you go around sweeping up and sorting out any last little snags.

The same thing with editing, where the hierarchy runs roughly like this, from big to small:

Developmental editing. Is this concept sound? Does my plot cohere? Are these the right characters for this book?Structural editing. Identifying and addressing any number of issues covering (for example) plot, pacing, characters, character development, settings, emotional turning points, themes, writing style and much else.Line editing: this starts to look at the detail. Is each sentence clear? Are there typos? Unwanted repetitions? Minor factual errors?Copy editing: much as above, except there’s less attention to line-by-line correction of clumsy writing.Proof reading: At the proof stage, you generally expect that all the essential work has already been done, so this is really just rushing around the manuscript looking for last bits of lint to pick off and typos to clear away.

That’s the overview. Not all manuscripts will go through all of these stages – indeed, if you’re doing a decent job as an author then two or three of these stages are probably redundant.

All that said, let’s jump straight into the meat…

Developmental Editing

We’ll start with the biggest, broadest, most sweeping kind of editing you can get: developmental editing. That’s a type of editing that used to have one meaning, but it’s kind of morphed into two distinct beasts for reasons, I’ll explain in a second.

Definition: What Is Developmental Editing?

In the good old days, developmental editing used to have one precise meaning. It now has certainly two, and maybe three.

A. Developmental Editing – Traditional Definition

But we start with the first, core, and most precise definition. To quote the ever-reliable Wikipedia:

“A developmental editor may guide an author (or group of authors) in conceiving the topic, planning the overall structure, and developing an outline—and may coach authors in their writing, chapter by chapter.”

In other words, any true “editing” took place before the writing. It was a planning and design function, in essence. Because competent authors can probably take care of planning and design perfectly well by themselves, such editing was always relatively rare and, in fiction, very rare. (I’ve authored getting on for twenty books now and have never once had a development edit. I’m damn sure I never will.)

B. Developmental Editing As Industry Euphemism

But of course not all authors are perfect and, now and again, publishers have to deal with a manuscript they’ve commissioned, but which turns out to be absolutely dire. Think celebrity memoir of the worst sort. Or a multi-million-selling author who’s long since stopped caring about how he or she writes, because they know the money will roll in anyway.

So what to do?

Well, the standard solution in trade publishing is to do what is euphemistically called a ‘development edit’. What that actually means is that an editor takes on the role of something akin to a ghostwriter. They rip out everything that’s hopeless and rebuild.

I’ve known a Big 5 editor who had done this a couple of times, and he said it was soul-destroying. He didn’t get any bonus for doing the work. He didn’t get a share of fame or royalties. He didn’t go on the chat shows or the book tours. And he was always dancing on eggshells with the Famous Author, because the author in question was very prickly about having his work slighted in any way.

Even though the work in question sucked.

Great.

So that’s the second meaning of a development edit: basically a euphemism designed to disguise what is basically a ghostwriting job.

When Is Classic Developmental Editing Right For You?

It isn’t. You don’t need it.

What you probably need (either now or in due course) is a professional manuscript assessment and possibly some of the add-ons normally associated with developmental editing. But in the classic sense of the term, you just don’t need it. We’ll talk about what you do need right away.

Structural Editing, Substantive Editing, Editorial Assessment

Right. So I’m not a big fan of developmental editing, but I LOVE the type of editing we’re about to talk about. But first up: definitions.

Definitions

Structural editing is, strictly speaking, a set of comments on the structure of your work. That will certainly involve plot and pacing. But it may also include comments on character, mood, emotional transitions, dialogue, character arcs, writing style and much more.

If you’re being strict about it, structural editing should focus only on structure, but in practice editors tend to comment on anything that, in their view, needs attention. (Which is good. Which is what you want.)

Basically, a good structural edit will tell you:

What’s working (though they won’t spend too long on this)What’s not working (this is where the report will concentrate all its firepower)How to fix the stuff that isn’t yet right

A good report will quite simply cover everything that you most need to know. It’ll do that from the perspective of the market for books as it is now. So the kind of crime novels (say) that could have sold 25 years ago may not be right for the market now. A good editor will know that, and set you on the right lines.

Substantive editing is basically the same as structural editing, except that technically it doesn’t have to limit itself to structure alone. But since structural editors don’t in practice confine themselves to structural comments, it’s pretty safe to say that, in practice, the two things are exactly the same.

Editorial assessment, or Manuscript assessment. These two things are exactly the same as structural editing. The difference is that an editorial assessment gives you an editorial report, but doesn’t usually also give you a marked-up manuscript as well.

Again, in practice, these things blur into each other. Our own core editorial product is, indeed, the manuscript assessment. The main deliverable there is a long, detailed editorial report on your book. That said, a lot of editors will, if it’s useful, also mark-up all or part of your manuscript. Or if they don’t, they may quote so extensively from your work, that it’s kinda the same as if they did.

In short, and give or take a few blurry bits on the edges:

structural editing = substantive editing = editorial assessment = manuscript assessment

Easy, right?

Is Structural Editing / Editorial Assessment Right For You?

Yes.

Almost certainly: yes.

Now, to be clear, I own Jericho Writers and if you trot along to buy one of our wonderful manuscript assessments, you’ll make me a teeny-tiny bit richer. So in that sense I’m biased.

On the other hand, I just told you not to buy developmental edits, and I’d make myself a LOT richer if I got you to buy one of those things, so I hope I have a little credit in the bank. I’m speaking truth, not salesman yadda.

And the reason I like structural editing so much is that:

It is and remains the gold-standard way to improve a manuscript. Nothing else has ever come close. I’m not that far away from publishing my twentieth book. (I’m both trad & indie, and I love both channels, in case you’re wondering.) I’m a pretty damn good author. I’ve had very positive reviews in newspapers across the world. My books have sold in a kazillion countries and been adapted for TV. And every single one of my books have had detailed editorial input. And they’ve always, always got better as a result. Always.It makes you better as a writer. You always emerge from these exercises with new skills and new insights. You will apply those to your current manuscript, for sure, but you’ll apply them to the next one too. The more you work with skilled external editors, the more you’ll grow as a writer. (And, I think, as a human too.)

So that’s why I think structural editing works so well, and for such a huge variety of manuscripts, genres and authors.

When Should You Get Structural Input On Your Work?

Well, OK. The businessman in me wants to say, “Get that input right now. Hand over your lovely hard-earned dollars / pounds / shekels / yen, and your soul and career will flourish, my friend.”

But that’s not the right answer.

The fact is that the right time for editorial input is generally: as late as possible.

If you know you have a plot niggle in Part IV, then fix the damn niggle. Fix it as well as you can. Don’t go and pay someone to tell you that you have an issue. That’s dumb.

Same thing if your characters feel a bit flat, or your atmosphere is a bit lacking, or whatever else. If you know your book has issues, then do the best you can to fix those issues. You’ll learn a lot and your book will get better.

That means, the right time for editorial input comes when:

You’ve worked hard, but you keep going round in circles. You’re confusing yourself. You need external eyes and buckets of wisdom.You’ve worked hard, but you know the book isn’t right. You don’t know what’s awry exactly, but you know you need help.You’ve worked hard, you’ve got the book out to agents, but you’re not getting offers of representation. You know you need to do something, but you don’t know what.The self-pub version of 2: you have a draft you’re reasonably happy with, but you’re about to publish this damn thing, and your whole future career depends on the excellence of the story you’re going to serve the reader. So you do the right thing and invest in the product. You’re going to get the best kickass structural edit you can, then use that advice as intensively as you can. (Editing, in fact, is one of the only two things that should cost you real money at this early stage: the other one is cover design. And, no surprise, they both relate to developing the best product it is in your power to produce.)

In short: work as hard as you can on the book. When you’re no longer making discernible forward progress, come to an editor.

And – blatant plug alert! – Jericho Writers is very, very good at editorial stuff. We’ve got a bazillion people published, trad and indie, and the success stories just keep coming.

Developmental Editing – As Premium Manuscript Assessment

I love manuscript assessments – I think they’re the single most helpful thing you can do to improve your work. At their best, with author and editor working well together, they’re like a magic formula for improving your work.

But a lot of people still find them insufficient. In particular, a manuscript assessment might say something like, “Your character Claudia isn’t yet cohering. Here’s what I mean in general terms [blah, blah, blah]. And here are some specific page references which illustrate my general point [page 23, page 58, etc].”

Now that’s helpful, but it still leaves you to do an awful lot. If Claudia is a major character, the specific changes you need to make are likely to go well beyond the handful of examples the editor uses to make their broader point.

So what do you do?

Well, hopefully, you understand exactly where your editor is coming from, and you make the necessary changes, and your manuscript becomes perfect.

Only maybe not. Some people just are helped by having their manuscript marked up page by page. That’s not instead of the more general report. It’s in addition. That way you get to see the broad thrust of the comments, as well as the more specific issues as well.

So you get an overview of (for example) why Claudia isn’t quite working as well as a detailed laundry list of all the specific places where her character grates a bit.

And it’s not just characterisation. It’s plot issues. It’s matters of writing style. It’s sense of place. It’s everything that goes into a novel.

So – and this is because our clients have specifically asked us to create the product – we now offer a version of developmental editing that combines these services in a single package:

Manuscript assessment – overview reportDetailed mark-up of your manuscript – literally page, by pageOne hour discussion with the editor, so you can resolve any outstanding questions or niggles you may have.

Pretty obviously, this is a deluxe package and, pretty obviously, it’s expensive. It’s also, honestly, not what most of you need.

Will I Benefit From Developmental Editing, Jericho-style?

As a rough guide, very new writers are probably best off building their skills by taking a writing course or, of course, just hammering away at their manuscript. (That’s still the best learning exercise of all.)

After that, once you have a first, or third, or fifth draft manuscript, it makes sense to get a regular manuscript assessment. That way, you can grasp the main issues with your work and you have a plan of attack for dealing with them.

Because developmental editing is as much concerned both with the broader issues AND with the narrower ones, it doesn’t really make sense to purchase the service until your manuscript is in pretty good shape.

After all, the outcome of a manuscript assessment might be “That whole sequence set on Venus just doesn’t work and needs to be rethought from scratch.” If that’s the case, then having detailed page-by-page comments on the way you write isn’t really going to help you much.

So as a rough guide, you will benefit from developmental editing, if:

Your manuscript is in pretty good shape (ie: this should be the last major round of work before submitting to publishers or self-publishing the manuscript)You want both broad and narrow commentsYou want the opportunity to talk at length with your editorYou are OK paying for a premium service.

You will not benefit from developmental editing, if:

Your manuscript is still at a somewhat earlier stage in its journeyYou feel able to handle the narrower issues yourself, so long as you have reasonable guidance from your manuscript assessment report.

Because we don’t want to take your money if developmental editing is not right for you, we have made the service by application only. That’s not because we’re going to stop you doing what you want to do. Just, if we’re not sure whether it makes sense for you to splash the cash, we at least want to be able to check in with you before we go ahead.

Line Editing, Copy Editing, Proof Reading

OK. We’ve dealt with the broader, more structural types of editing. We’re now going to home in on the ever finer-grained types of editing.

We’ll start as before with some definitions.

Definitions

Of the detailed, line-by-line type edits, line-editing is the one that has the broadest remit. I’ll start with proof-reading (the most narrowly defined of these editorial stages) and build upwards from there.

Proof-reading comes at the final stage prior to printing/publication. It basically assumes that the manuscript has already been checked over thoroughly, so this is really only a final check for errors that have managed to slip through the net. (And, in fact historically, the process of type-setting for print often introduced errors, so proof-reading was partly necessary to reverse those. These days, unsurprisingly, you can format a document for print without messing it up.) The kind of errors a proof-reader will catch include: typos, misspellings, punctuation errors, missing spaces, and the like. It’s a micro-level, final-error catching task, and nothing much else.

Copy-editing includes everything included in proofreading, but it’ll have a somewhat broader scope. So a copy editor will also be on the look out for factual errors, timetable and other inconsistencies in the novel, occasional instances of unclear or weak phrasing, awkward repetitions, deviations from house style (if there is a house style), and so on. In the traditional publishing sequence, copy editing will take place after all structural editing has been done, but before the book has been set for print.

Line-editing will cover everything that’s detailed above, plus a general check for sentence structure, clarity and sense. In other words, it is part of a line editor’s job to fix clumsily phrased, repetitious or otherwise awkward sentences. Yes, you the author should not be writing clumsily in the first place, but if by chance you do, the line editor is there to put things right.

Why does anyone ever want or need line-editing? Well, some authors are brilliant at generating character and story, but their actual sentence-by-sentence expression of that story just isn’t so great. In these cases, a publisher will commission a line-edit to put those things right.

The Editing Process: What You Need & When You Need It

Right. What kind of editing you need and should pay for depends on what kind of publication you are looking at. So:

The Traditional Publishing Sequence

The normal publishing sequence (for traditionally published books) would be:

Structural editing (ie: a detailed manuscript assessment)Copy-editing (or line editing if the author really needs it, but never both things)Proof-reading

That’s it.

If you are aiming at traditional publication, then you may well need to invest in a manuscript assessment, in order to write something of the quality needed for a literary agent / publisher.

You certainly won’t need copy editing, or anything along those lines. That’ll be carried out, for free, by the publisher down the line. (They’ll also do some more structural editing work too, but don’t worry about that – you can’t get too much, and your book always gets better.)

The Indie Publishing Sequence

Indie publishers, inevitably, focus more on cost-cutting than the Big 5 houses do, so a typical indie process might look simply like this:

Some kind of structural support – probably an editorial assessment or something similarSome kind of copy-editing support

If you don’t have the budget for both, I’d urge you to get the structural help: that’s what will really make the difference to the sheer readability of your book. That’s where to spend your funds.

Indeed, though we at Jericho Writers offer a full range of copyediting and proofreading services, I don’t usually advise writers to invest in them at all.

If you are an indie on a lowish launch budget (which is the right kind of budget to have when you’re just starting out), then I’d recommend an editing plan along roughly the following lines:

Full editorial assessment, ideally from Jericho Writers (because we’re really good at it.)You then rework your book in the light of what you’ve been toldYou then give it a good hard proofread yourself for any errors and typosYou then enlist the help of any eagle-eyed friends to do the same

That plan won’t give you a manuscript as clean as if you give it the full cost-no-object Big 5 treatment … but it’ll be just fine. Don’t overspend at this stage.

The Indie Publishing Sequence

OK. You know the basic layout of what editing is and when it’s used. Here’s what I think the big questions are.

Developmental Editing Vs Structural Editing

You know my view on this. I think for 99% of you reading this, you are best off (a) working and self-editing as hard as you can yourself, then (b) getting professional input on your work from a structural editor.

That’s going to be miles cheaper and the end result will be better too. Yes, you’ll need to do a lot of work, but you’re a writer. You like work. (If you don’t, you’re in the wrong job.)

If you are a newer author, you may well need two or three rounds of structural input. That’s fine. That’s not a failure on your part. That’s you learning a new trade. It’s money well spent – and you can prove it to yourself too. Just ask yourself: are you a better, more knowledgeable, more capable writer at the end of the process? If the answer isn’t yes, I’ll eat my boots, jingly spurs and all. (*)

* – disclosure: I don’t actually wear spurs.

Structural Editing Vs Copy Editing

OK, these are two very different things, but of the two, the structural editing definitely matters more. The purpose of structural / substantive editing is simply: make your book the best book it can be.

The purpose of copy editing is simply: make the text as clean as it can be.

Both things matter, but if your budget only permits one of those things, then go for structural editing, every day of the week. A wonderful story is much more important than tidy text.

And again, though we sell copyediting services, you shouldn’t need them at all if you are heading for trad publication, and you should probably be able to find an acceptable but much cheaper substitute if you are self-publishing.

Line Editing Vs Copy Editing Vs Proof-reading

If you are going to get line-by-line corrections to your MS, then the default answer is to go for copy editing. Proof-reading is really too narrow, and only really makes sense if your book has already been copy edited. (Which is fine if you have a Big 5 budget, but makes no sense for you.)

Line editing is really only required if your sentence construction isn’t yet all it could be, in which case I’d urge you to invest in upskilling. Quite simply: as a pro author, you should be in command of your language. If you’re not, and have to pay a line editor, and if you intend to write 10, 15, 20 or more books over the course of your career, you’ll end up paying a fortune. Much, much better to nurture those exact skills in yourself, and you’ll never need to spend a penny on a line edit.

Also: writing well is good for your soul and writing beautiful sentences is a source of beauty and joy forever. So don’t give anyone else the pleasure.

And Finally…

That’s it from me. Thanks for reading. If you’ve read this far, you may also like:

Help on how to present your manuscript

Help on how to self-edit your novel

If you need help figuring out what kind of editorial process (or, indeed, other support) might be right for you, then get in touch. Jericho Writers does not have a sales team or employ salespeople or pay anyone on commission. Our customer service people are only allowed to recommend a particular service if they genuinely think it would be helpful to the writer concerned.

We’re run by writers for writers, and we’re on your side.

Thanks for reading – and happy editing!

Jericho Writers is a global membership group for writers, providing everything you need to get published. Keep up with our news, membership offers, and updates by signing up to our newsletter. For more writing articles take a look at our blog page or join our free writer\'s community.

If you think you need copyediting for your manuscript, take a look at our copyediting services. Jericho Writers\' experienced editors specialise in editing both novels and non-fiction and would love to help you with your work. Click here for more.